For many, this may bring up images of dead plants and brown shrubs in addition to shorter showers. But for those loath to let their landscapes shrivel, water conservation advocates are pointing to a different option: greywater systems, a relatively inexpensive solution that they say is gaining interest but is still relatively little known.

Greywater systems take water drained off from laundry machines, sinks or showers and repurpose it to irrigate parts of their landscapes. The simplest systems can be installed for a few hundred dollars as a do-it-yourself project — an investment, experts say, quickly recouped in water bill savings.

The technology isn’t new — greywater systems have been around for decades. But experts note that California, a state long familiar with extreme drought, still doesn’t have statewide incentives for people to install systems that can save thousands of gallons of water each year for a family of four.

“There is no real blanket guideline available right now, and there are not a lot of incentives out there either to get people to do this,” said Newsha Ajami, a water expert at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory who had served on the Bay Area Regional Water Quality Control Board.

On a local level, incentives are not robust in the Bay Area either. Santa Clara County offers a $400 rebate through Valley Water, San Francisco offers $225, Contra Costa County and the East Bay Municipal District each offer up to $50, and other counties and water districts offer none at all.

Statewide, landscape irrigation accounts for about 50% of annual residential water consumption, according to the University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

In the face of drought, all that water can be put to better use, experts said.

“Our plants don’t need drinking water,” said Justin Burks, a water conservation specialist at Valley Water.

Piping is laid out in the front yard before a greywater installation demonstration at a Vallejo home.

Brittany Hosea-Small/Special to The Chronicle

A 2012 study by Bay Area-based advocacy group Greywater Action found that homes in the Bay Area and Monterey County that installed greywater systems reduced their per-capita daily water consumption by an average of 17 gallons, for an average household savings of about 14,500 gallons a year.

Another benefit: Using greywater means people can continue to grow plants and trees in their yard — which can provide food and shade and support wildlife — rather than ripping them out in the face of water restrictions, advocates said.

But while greywater has been shown to save both water and money, advocates and experts note that it’s faced a number of challenges to more widespread adoption over the years.

Burks noted that many people want a solution that’s “off-the-shelf” — one that they can easily switch to without making any other changes. But greywater systems don’t always fit the bill.

For example, the simplest laundry to landscape systems, which don’t involve a pump and a filter, produce water containing chemicals and dirt that can’t go into storm drains and sewers. As a result, they can’t be used for surface watering, meaning they won’t save your lawn. They also can’t be used to water vegetables if the edible part is in contact with the soil — like lettuce, strawberries or carrots. Instead, they pipe water into mulch basins around trees and shrubs, where the mulch itself acts as a filter.

And if the pipe gets clogged — which experts and advocates noted is rare, even with minimal maintenance — the backed-up water can get smelly, fast.

Using greywater also requires people to use a biodegradable laundry detergent, and bleach is prohibited — though you can turn the pipe off if you need to run a load with bleach or other more chemical detergents, experts said.

Nina Gordon-Kirsch, with Greywater Action, explains the process for digging mulch basins during a greywater installation demonstration at a Vallejo home.

Brittany Hosea-Small/Special to The Chronicle

Other greywater systems have complex filtration and can repurpose shower water as well as laundry runoff to irrigate lawns and more diverse types of plants. However, these options require permits and become expensive quickly — costing up to thousands of dollars.

For years, reusing greywater was illegal, largely because it was treated the same as blackwater, or wastewater from toilets. In the 1990s, California changed its plumbing code to allow legal reuse of greywater, but still had significant restrictions on what that could look like.

In 2009, California allowed the installation of simpler greywater systems, like the laundry-to-landscape model, without a permit, so long as certain requirements were met, making it much more accessible, said Laura Allen, a founding member of Greywater Action who has been working on the issue for decades.

That’s the moment, she said, that finally opened the door for more professionals and government agencies to really begin focusing on the systems.

But there are still lasting misconceptions about greywater, she said.

Some critics worry that greywater is unsafe and could contaminate soils, which could have effects beyond just a person’s backyard. But advocates say evidence so far has shown that’s not the case — and that greywater can actually be beneficial for life in backyards.

Greywater Action’s 2012 study, for example, looked at 83 greywater systems in the San Francisco and Monterey Bay areas and found that they did not affect soil salinity, boron or other nutrient levels when compared to soils that had not been irrigated with greywater.

More recently, in her 2021 master’s thesis for San Jose State, water researcher Sara Khosrowshahi Asl found the same thing — that greywater did not negatively impact soil quality, and in fact, for systems that had been in place longer, soil quality actually improved, as more nutrients were able to build up.

She explained that the most successful greywater efforts employ biodegradable or greywater-friendly detergent, which she found most people use.

“You don’t need to add fertilizers anymore,” she said. “Just the detergent itself and the things that are in the clothes add the nutrients to the soil.”

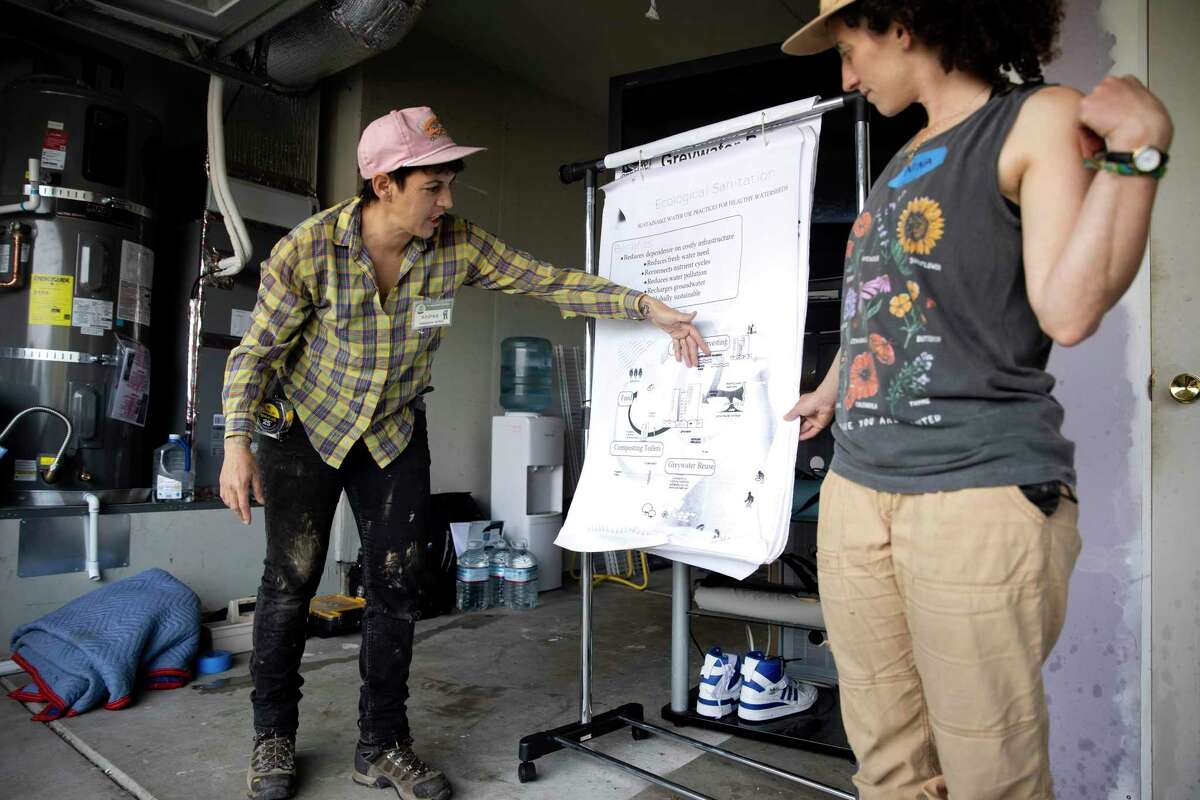

Andrea Lara (left) and Nina Gordon-Kirsch, both with Greywater Action, talk with local community members during a greywater installation demonstration at a Vallejo home.

Brittany Hosea-Small/Brittany Hosea-Small / Special to The Chronicle

Another obstacle to more widespread adoption of greywater systems is California’s water distribution system itself, said Ajami, the Stanford water expert.

She said that many water providers have already invested in larger-scale recycled water systems, which makes them less inclined to provide incentives for people who want to recycle their own water, because it would reduce the amount of water going to a centralized recycling plant.

“Their business model is not made for this kind of solution,” she said, in the same way electric utilities put limitations on people’s solar use.

Joseah Rosales, whose company Greywater Landscape Design helps people in the Bay Area and San Diego install greywater systems, said the patchwork of rebates makes things more confusing for those looking to add a system and need some help with the cost.

But the larger challenge, many advocates and experts said, is just how few people even know about greywater in the first place.

Advocates and policymakers point to Valley Water as offering one of the best opportunities for those looking to get into greywater. The South Bay water agency offers up to $400 to people installing a laundry to landscape system — the highest in the Bay Area — and has done so since 2014.

But, in those eight years, only 142 customers have taken advantage and built a system, said Burks, the water conservation specialist at Valley Water — which according to its website serves nearly 2 million people.

“That’s pretty impressive compared to most agencies, but it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the literally hundreds of thousands of potential properties in the county that could benefit from a laundry-to-landscape system,” he said.

As for what’s holding people back, he said that for one, many people aren’t aware that it’s an option. Compared to something like solar panels on a roof, greywater systems are much more inconspicuous, he and other advocates said, which makes them likely to arise as a topic of neighborly conversation.

“More people getting out there and talking about their system is going to be really paramount” to increasing the number of greywater systems statewide, he said.

And while laundry to landscape greywater systems can be installed as a DIY project — and there are workshops from various Bay Area groups who show it — it isn’t exactly simple. And even for those who can afford someone to install it, there aren’t enough installers to go around, experts said.

Andrea Lara (left), with Greywater Action, shows volunteer Alex Lunine how to tape a pipe fitting during a greywater installation demonstration at a Vallejo home.

Brittany Hosea-Small/Special to The Chronicle

Rosales said that demand goes up with every drought, and there aren’t very many companies like his that focus on greywater.

Nicole Newell, who helps people install greywater systems through community group Sustainable Solano, said that each time her group conducts tours of its sustainable backyards, people express interest in greywater. But for those who don’t feel equipped to do the installation themselves, it can be hard to find help.

“Our challenge is that there’s not a ton of people doing this work,” she said.

The Bay Area Water Supply and Conservation Agency, which assists more than two dozen water suppliers in San Mateo, Santa Clara and Alameda counties with planning, conservation and other programs, is creating a pilot program in response to “the increasing interest in greywater programs regionally,” according to a board agenda item earlier this year.

Tom Francis, the agency’s water resources manager, said he sees a lot of opportunity in greywater systems — though he acknowledged that maybe “pilot” isn’t the right word, since greywater systems have long been proved to work. He said he hopes the program, by collecting detailed data on water savings and the cost of the systems, will give smaller water agencies more confidence and more information with which to create or improve their greywater programs.

But, like others, he said that much of the work essentially comes down to marketing.

“As water agencies, we’ve got to do a better job in selling it,” he said. “We’re so environmentally conscious here in the Bay Area, compared to any other place, I’m kind of surprised that more residents at least aren’t aware of it.”

Danielle Echeverria is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @DanielleEchev

[ad_2]

Originally Appeared Here