Indoor air quality, to some degree or another, has been a concern since at least the 1960s, when the term “sick building syndrome” began making its way into the public health conversation. It refers to a list of “non-specific” illnesses brought on by time spent in a particular enclosed environment. It wasn’t a huge concern then, and frankly, even when it became a bigger part of the conversation in the ’80s, it still wasn’t. But that’s history.

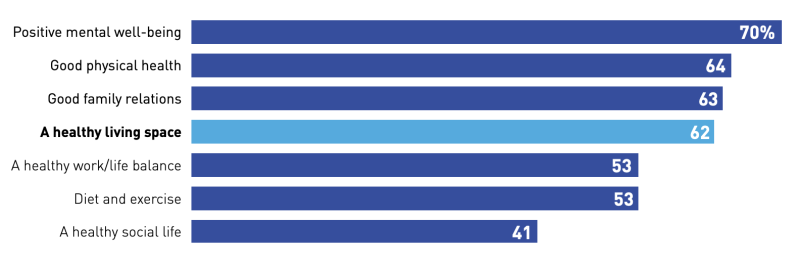

Today, nearly three years into a global pandemic brought on by a respitory illness, a heatlhy home and more specifically indoor air quality is at the forefront of homeowners’ minds. It’s a top priority now, according to a survey from Panasonic, which found that nearly two-thirds of homeowners consider a healthy living space a chief concern when it comes to their personal well being. And for people like Dr. John McKeon (pictured), a former ER doctor who in 2000 founded Allergy Standards, a organization aimed at improving air quality throughout the built environment, that line of thinking couldn’t have come soon enough.

Unfortunately, there may now be a disconnect between what builders and remodelers think hurts and, further, improves indoor air quality, and what actually impacts it. The goal of Allergy Standards, at least in part, is to attempt to bridge that gap.

We caught up with Dr. McKeon and asked him to tell us more about Allergy Standards, indoor air quality, home construction, and how it all fits together.

Residential PRODUCTS Online (RPO): You are the founder and CEO of Allergy Standards. What led to that?

Dr. John McKeon (JM): I was an emergency room doctor, and patients with allergies and with asthma would have to come in their moms, and the moms would ask, “Is there something we can do to stay well rather than having to come in and you treating us?”

Being well isn’t just about the absence of disease. It’s about actually being well. Physically well. Emotionally well. It’s becoming a big part of our life. We all wear wearables. We talk about our steps. And with the pandemic, the whole concept of indoor air quality is very much on people’s minds. We spend about 80% of our time indoors in the built environment. Scrutinizing material science and ventilation is an idea we’re very tuned into. We’re spending more time in our homes, where, thinking about trigger factors, you’re talking about Bioburden allergens, mold, biological pollutants, and moisture mold in the indoor environment. You’re also talking about chemical irritants.

I would answer parents’ questions and give them advice about how to configure their built environment. And they would write it down so they could rely less on doctors and less on medication. The problem is that the concept works, but it’s quite complicated.

You think about furthest filters in the textiles and the paint, and so not everything. We bring into it the incidental furniture now, the actual building envelope, and how we construct those buildings, the insulation and floor coverings and paint, and so forth. It was one of those eureka moments, where I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great if there was a logo? If somebody tested products to confirm if they’d help improve the indoor environment, and if they remove allergens, or don’t contain irritants? Then you can actually certify those products like kosher food or organic food, or any of those other kinds of food-related logo programs.”

You think about furthest filters in the textiles and the paint, and so not everything. We bring into it the incidental furniture now, the actual building envelope, and how we construct those buildings, the insulation and floor coverings and paint, and so forth. It was one of those eureka moments, where I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great if there was a logo? If somebody tested products to confirm if they’d help improve the indoor environment, and if they remove allergens, or don’t contain irritants? Then you can actually certify those products like kosher food or organic food, or any of those other kinds of food-related logo programs.”

So that was the model.

RPO: And how now does that initial model look translated into real-world action?

JM: We have third party testing verification protocols. We started by looking at all building materials in the built environment. Once we had the parts in place, we partnered with patient organizations—which in America is the Asthma And Allergy Foundation of America—and launched the certification program. As we grew and developed, we started testing children’s toys and then later electrical and vacuum cleaners, air filters, and more and more things that are present in the built environment.

We’re now actually looking at the built environment as a whole, and we’re doing training for building professionals. We did a joint venture with EEBA, the Energy Efficient Building Alliance, and we’ve done one with the ISSA, the facilities management people with BOMA, the Global Biorisk Advisory Council, and more.

And then we’re actually looking into doing some clinical studies. Answering the question: If you install and use all healthy products, build a healthy environment, and then people live in that environment, are they actually healthier? Can you measure health impact outcomes?

RPO: Allergy Standards has proliferated quite a bit since its founding in 2000. You’ve got your logo in a lot of product categories. That growth seems to align with the public’s seemingly rising interest in indoor air quality. Have you felt that same increasing focus on indoor air quality?

JM: The answer is yes. There’s no doubt about that.

When asked what is most important to their personal well being, a majority of homeowners responded, “a healthy living space.”

Source: Panasonic Industry Survey

RPO: The pandemic clearly stoked that concern over the last few years, but it had been growing for decades before. What are the big, long-term influences driving that concern?

JM: The whole concept of sustainability has moved beyond planet to people. If you think about it historically, it has largely been sustainability and the green certification systems. But now we’re analyzing a product’s lifecycle, the impact we have on the environment when we make something as well as the impact we have when we throw that something, or anything, away.

Of course it’s important to have responsible wood and not to damage the rainforest. We’re widely thinking about building the home out of sustainable materials that are good for the planet. But that’s almost table stakes, the basics. People are now starting to really ask, “is that home good for me?” I believe people have moved beyond planet friendly to include people friendly in that equation.

Obviously, this has been accelerated by the pandemic. But it’s also a natural progression. If you have smart technology where your toasters are connected to your fridge, or whatever, people will say, “That’s great. It’s efficient and smart.” But now they may also ask, “Is it also healthy?”

It was always a natural progression, but it was massively accelerated by the pandemic.

RPO: When you think of specifically building materials, where are the big pain points for builders? What what types of materials are really making the biggest, most negative impact on the home potentially?

JM: I’d say, in a slightly dodging your question kind of way, is that builders shouldn’t be thinking in isolated terms of specific materials, like just flooring as a paint point. We should be thinking of building as an integrated management system. Even the incidental furniture we bring in can break a build.

RPO: Talking about indoor air quality. I think a lot of builders and remodelers aren’t necessarily up to speed on the science, or even the nomenclature, that links building materials and indoor air quality. Talk to us about some specifics, like the role humidity plays in air quality.

JM: Well, first of all, you’re right there. There is a real gap in the knowledge. Last year I went to a building show in Orlando, and then two weeks later went to a major allergy-related medical event.

There was a healthy home module at the building show, and there was also a healthy home module at the medical one. But there were no builders at the medical one, and no doctors at the build show. So there is a real problem, especially with the nomenclature. You’ve got a group of people actually designing and building homes that don’t know much about health. And you’ve got all of these doctors concerned with health, but they know nothing about the design industry.

We’re trying to be a bridge between those two communities.

But to answer your question, moisture is a big issue. Too little moisture leads to dry air and that’s an irritant to mucous membranes. Too much moisture can lead to dampness and eventually mold, which harbors bacteria. There are also indoor pathogens, which can make somebody very sick, very quickly—either through an infection or an allergy. So balancing moisture is really important.

On its website, Allergy Standards features a database of its certified products, featuring selections from a range of popular categories, including

Image: Allergy Standards

RPO: In what product categories is Allergy Standards most reviewing products?

JM: You think of somebody’s home: You probably spend the most amount of time in the bedroom, and people are very switched on about sleep now—recharging, detoxing, avoiding chemicals and noise and things like that. So textiles and bedding, mattresses, pillows, those kind of incidental furniture are big for us—and definitely something that’s good for designers to know.

Laundry is another big one. It’s really important for fabrics and textiles, removing allergens from your clothes, your pillows, sheets and things like that.

We also do a lot with floor coverings, paints, furnaces, air handling, appliances, and whole-house filtration systems. We with a lot of manufacturers, like Trane, 3M, and LG, to name a few.

RPO: I’ve seen a lot of products, a lot of paints and appliances especially, thatare now incorporating antimicrobial and antiviral coatings. Have you looked into any of the science behind those? Is that an effective strategy for making a home healthier?

JM: There is a role for some of those products; though, I think more research needs to be done. Mostly to answer: are they really necessary?

If you have a floor floor covering, for example, fairly basic cleaning chemicals will remove 80 to 90% of packages. And it’s unlikely you could have a really nasty MRSA or any of those hospital pathogens in a home. I’m not convinced that basic cleaning practices are so insufficient that these coatings are needed. More likely there is a role for them in specialty environments, such as for people that are immunocompromised.

RPO: To wrap us up, one thing you mentioned earlier was training professionals and acclimating people to the science of it all. Can you just talk a little bit about the resources that are available to residential construction professionals who are more interested in this type of education?

JM: Absolutely. We have a wide range of resources available through our website, including a database of certified products. We also offer a number of training programs available through our Allergy Standards Academy.

Partnering is also an important part of what we do. We’ve partnered with Construction Instruction and EEBA, both of which offer additional resources through their respective websites.

[ad_2]

Originally Appeared Here