Uncertainty and new questions are some of the first things that come to mind for Katherine Dickinson, PhD, assistant professor of Environmental & Occupational Health at the Colorado School of Public Health, when recalling Dec. 30, 2021 – the day of the Marshall Fire.

“Afterward, I tried to write something and then had to take a step back,” said Dickinson, whose home was in the path of the state’s most-destructive fire in terms of structures lost. “I’m still processing my own experience.”

|

NASA satellite imagery from Dec. 30, 2021, showing the intensity of the Marshall and Middle Fork fire smoke plumes. |

The day of the fire, Dickinson and her family were driving back from the mountains and rerouted to her grandmother’s house in Longmont after receiving calls and texts. The rest of the day brought an anxious wait. She could only watch the news and smoke in the sky as they waited to hear about their home and the status of friends and family.

With the snow that fell less than 24 hours after the Marshall Fire began, a new stage of response and recovery started that is central to Dickinson’s professional career: How do you balance the realities of forward-thinking climate change policy with the immediate challenges after a disaster?

Dickinson and colleagues at the CU Denver and Boulder campuses are seeking to answer those questions and more.

Professional and personal lives intersect

Like many members of the CU community, the Marshall Fire was personal for Dickinson. Her family lives in Louisville and her husband is a city council member.

“We definitely had a few really scary hours where we didn’t know if this house was going to be here,” Dickinson said from her home, which was spared from the flames.

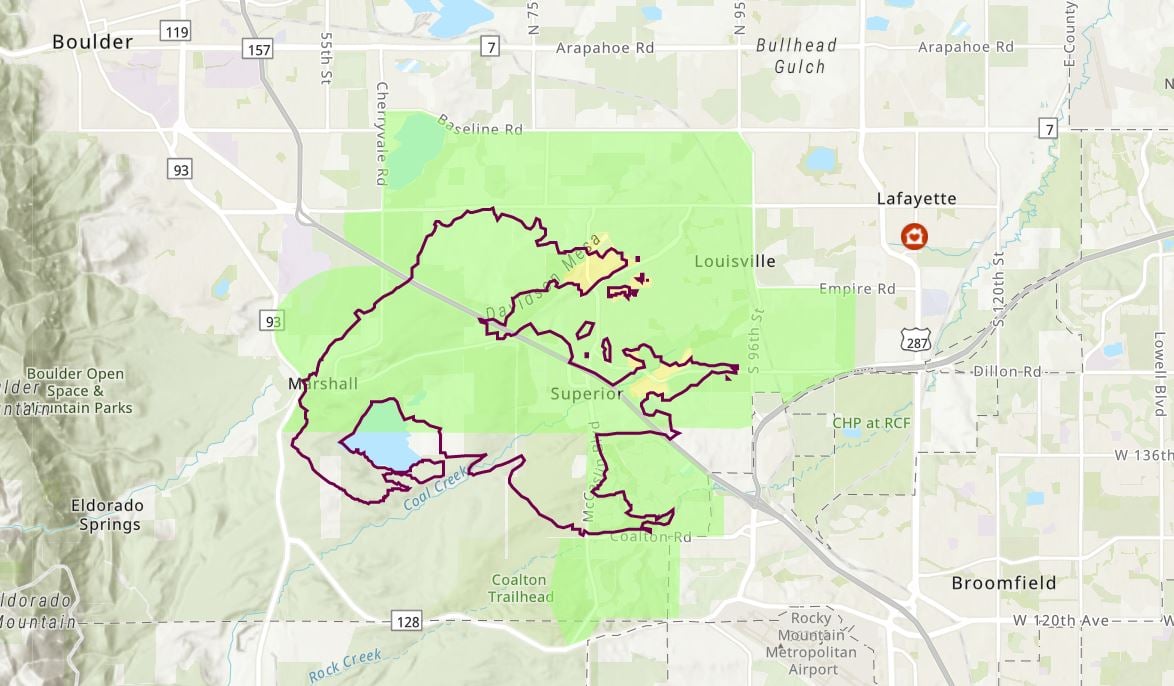

Map of the Marshall Fire burn area and affected neighborhoods from the Boulder Emergency Operations Center. |

After being allowed to return to their neighborhood, Dickinson said one of the things that stood out was the random element of the fire. “Just any small shift in the wind, and the house could have gone. And then, who knows?”

With a research background in environmental economics, Dickinson’s experience hit home in many ways.

“I think a lot about policy and individual risk perceptions and behaviors,” she said. “I’ve actually done research in the past on wildfire mitigation behavior in the ‘wildland urban interface,’ which we didn’t think we were in. I’m kind of alternating between my resident hat, my mom hat and my researcher hat.”

Dickinson and her colleagues have submitted a National Science Foundation Rapid Response proposal on how local resilience policies change post-disaster.

|

A charred fence on the Oerman-Roche Trailhead overlooking homes destroyed and spared by the Marshall Fire near the Superior Town Hall. |

Local response in the time of climate change

As both a community member and public health researcher, Dickinson wants to know:

- What does a local government do in the wake of a disaster?

- How do different levels of government work together to care for a traumatized community?

- How is residents’ support for climate resilience policies shaped by their own personal experiences after disaster?

After the tragedy, the direction of civic planning and urban design are among the complex issues being raised. Dickinson points to building codes as one example of those complexities. In November 2021, the Louisville City Council passed new sustainable building codes for future structures built in the city.

“And the idea was, all communities need to step up and really take action to reduce our climate emissions, our carbon footprint. And the building sector is one of the places where we can do that,” Dickinson said. “And so let’s push new buildings in this area to comply with these building codes to make them as climate friendly as possible.”

“It doesn’t matter how affluent and privileged you think you are. Climate change is

coming for all of us.” – Katherine Dickinson, PhD

But following the Marshall Fire – especially when many homeowners don’t have access to their home’s original building plans – many in Louisville and Superior have expressed concerns about the cost of rebuilding.

Dickinson believes that a more complete understanding of the risks Colorado communities face needs to be part of the conversation. She lists building materials and property design for homeowners who are adjacent to open space – specifically not having wooden fences to fuel fires – as just two examples of a growing number of conversation points that need discussion.

The remains of a home near Dillon Road in Louisville. |

A collaborative Colorado response

Dickinson is working alongside researchers at CU Denver and CU Boulder, including those at the Natural Hazard Center, as part of the larger, collective effort to study the effects of the Marshall Fire.

Early efforts are encouraging, Dickinson said. Because so many experts either live or work alongside Marshall Fire-affected colleagues, it is spurring unified action to answer questions about the fire – all while trying to ensure minimal impact to the communities affected as they work to recover, she said.

Avery Hatch, a CU Boulder PhD student in environmental engineering, conducting indoor air-quality tests in a home in Superior. |

“There are folks that want to come and help,” Dickinson said. “It is something to manage, but I think overall, I really see the city being like, ‘This is awesome.’”

Teams are looking at such critical issues as air quality, building materials and how they might affect fire behavior, and gaps in the emergency warning system, she said.

Her own research will focus on the nature of the risks communities face, understanding those risks and how that understanding influences government policy and communities’ role in combating climate change – all with a focus on equity, Dickinson said.

“Processes of environmental injustice have divided our society and allowed us to create this illusion that some places are going to be harmed and other places are going to be OK,” Dickinson said. The focus needs to shift, looking at climate change as a threat to society as a whole, including the most vulnerable, she said.

“What can we do to make sure that those vulnerable folks in our society are OK? We need to recognize that those actions will ultimately make all of us safer. It doesn’t matter how affluent and privileged you think you are,” Dickinson said. “Climate change is coming for all of us.”

Banner image: Louisville, air-quality testing photos. Credit: CU Boulder

[ad_2]

Originally Appeared Here