A warming climate means millions of Americans are exposed to wildfire smoke every summer. Seattle, Wash., and the Pacific Northwest experienced some of the worst air quality in the world in 2020.

When wildfire smoke descends over a city or town, as it does increasingly often for tens of millions of people in the American West, public health officials have a simple message: Go inside, shut doors and windows. Limit outdoor activities.

New research shows that may not be enough to protect a person’s health.

A series of studies looking at crowdsourced indoor air quality during wildfire smoke events has found that the most insidious part of wildfire smoke — microscopic particles so small they can infiltrate a person’s bloodstream, exacerbating respiratory and cardiac problems — can seep through closed doors and shuttered windows, making air hazardous in homes and businesses.

The research shows, in detail for the first time, the depth of the public health risk millions of Americans are being exposed to every climate-fueled fire season. But the findings are also encouraging in that they show there are steps people can take to protect their health.

Homes that used air filters, in addition to closing windows and doors, were able to cut the amount of those tiny PM2.5 particles floating inside them by half, according to research from the University of California, Berkeley.

“While the particulate matter indoors was still three times higher on wildfire days than on non-wildfire days, it was much lower than it would be if people hadn’t closed up their buildings and added filtration,” said the study’s senior author Allen Goldstein.

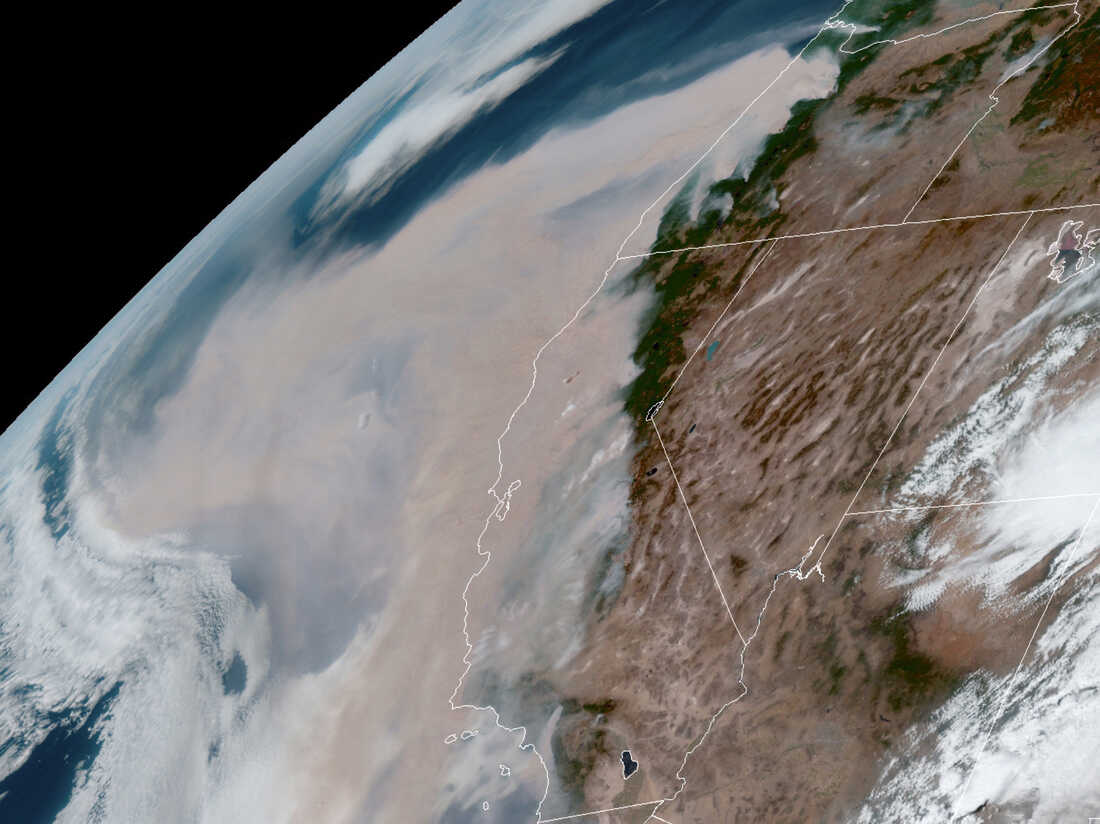

Brown smoke from wildfires blows westward in the atmosphere from California and Oregon on Sept. 9, 2020. Smoke from Western fires has triggered air quality alerts 3,000 miles away.

Brown smoke from wildfires blows westward in the atmosphere from California and Oregon on Sept. 9, 2020. Smoke from Western fires has triggered air quality alerts 3,000 miles away.

But the results, like many of climate change’s impacts, were not equal.

Newer homes, better insulated and equipped with air filters, did better than old ones, highlighting the need for air filtration for people who live in drafty homes.

That includes Marshall Burke, an earth system scientist at Stanford University and the author of a similar study scheduled to publish later this fall. During last year’s unprecedented fire season, his home was enveloped in smoke for weeks like many others in the Bay Area.

“And I have two kids, one who’s asthmatic, so I’m really worried and interested in what those [indoor] exposures look like,” he said.

He bought a low-budget PurpleAir monitor that reads indoor air quality and publishes it online.

“And our indoor pollution was sky high during these wildfire events,” he said.

He looked at other people’s data shared by PurpleAir monitors and found that was the case across California. In fact, oftentimes, the air inside was just as bad as it was out. The findings startled Burke and worried him.

“Fortunately, I have the means to go buy an air filter,” he said. “That’s not the case for everyone.”

The Staten Island Ferry departs from the Manhattan terminal through a haze of smoke from Western wildfires, with the Statue of Liberty barely visible on July 20.

Julie Jacobson/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Jacobson/AP

The Staten Island Ferry departs from the Manhattan terminal through a haze of smoke from Western wildfires, with the Statue of Liberty barely visible on July 20.

Julie Jacobson/AP

The number of people exposed to wildfire smoke is growing

At least 1-in-7 Americans experienced dangerous air quality from wildfire smoke last year, an analysis by NPR found. Tens of millions of more have been directly exposed this year, as massive wildfires have torn across Canada and the West’s drought-wracked, heat-baked landscapes.

The smoke triggered air quality alerts 3,000 miles away, enveloping the Statue of Liberty in a grey haze.

Scientists are just starting to get a better understanding of smoke’s effects on human health. What they know so far isn’t good.

A warming climate means higher intensity wildfires, more frequently. And where there’s fire, there’s harmful smoke.

A study by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, published earlier this year, found that tiny particles released in wildfire smoke are up to 10 times more harmful to humans than particles released from other sources, such as car exhaust.

Wildfire smoke blankets Missoula, Mont., at the end of a hot summer day. The mountain town has been inundated with smoke for weeks this summer.

Nathan Rott/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Nathan Rott/NPR

Wildfire smoke blankets Missoula, Mont., at the end of a hot summer day. The mountain town has been inundated with smoke for weeks this summer.

Nathan Rott/NPR

Those tiny particles have been shown to increase hospitalizations, cause shortness of breath and headaches, and can trigger bigger respiratory or cardiac events.

Because of those known threats, public health officials have long been warning people — particularly at-risk populations — to seek shelter when smoke is thick.

But the new research suggests that there needs to be an additional step.

The public messaging during a smoke event needs to change, says Sarah Coefield, an air quality specialist in Western Montana, “from ‘Go inside,’ to ‘Go inside and clean your air.’ ”

Coefield helped author a study with the Environmental Protection Agency that looked at air quality inside public buildings and businesses during wildfire smoke events in Missoula, Mont. They placed air monitors in daycares, schools, libraries, businesses and other publicly accessible buildings — the types of places that health officials like Coefield generally recommend people go to during smoke or heat events.

“We did not have a single building with air that was, like, significantly better than outside,” Coefield said. “Some of the buildings, you might as well have been outside.”

There’s a push to help provide clean indoor air for everyone

Mason Dow, a member of Climate Smart Missoula, gives a free air filter to a new mother at a local food bank, explaining the impacts of wildfire smoke on human health.

Nathan Rott/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Nathan Rott/NPR

Coefield agrees that air filters are the logical answer. But they cost money. A fancy HVAC system for a school can cost thousands of dollars. An air filter for a home can cost hundreds.

Knowing that some people don’t have the financial means to afford that kind of protection, there’s a growing push in the environmental justice and climate change movements to make sure everyone has access to air filtration.

On a smoke-filled, hot day in Missoula, Mason Dow and a group of volunteers duct tape square air filters, bought at Home Depot, to a stack of box fans. The materials for each cost about $40.

Dow works for a local nonprofit called Climate Smart Missoula that usually focuses on legislation and policies to reduce people’s contribution to climate change. With the effects of a warming world already being felt though, Dow said, it was important to step in and help people adapt to its effects.

“That’s just the reality of where we are,” he said.

The DIY air filters are given to volunteers working for Meals on Wheels and are distributed at the Missoula Food Bank, targeting the booming mountain town’s lower-income residents, who often don’t have air conditioning either.

Sixty-seven-year-old Janet Friede is one of those people. She’d been keeping her doors and windows closed during heatwave after heatwave this summer, but the smoke keeps getting through.

“It makes me have a headache,” she said, loading a box fan filter into her car. “And tired. Real tired.”

The free air filter, she said, should hopefully help.

Amy Cilimburg, the executive director of Climate Smart Missoula, says nonprofits like hers need to help people adapt to a warming climate — not just to limit their greenhouse gas emissions.

Nathan Rott/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Nathan Rott/NPR

Amy Cilimburg, the executive director of Climate Smart Missoula, says nonprofits like hers need to help people adapt to a warming climate — not just to limit their greenhouse gas emissions.

Nathan Rott/NPR

“It feels maybe a little bit like a band-aid,” said Amy Cilimburg, Climate Smart Missoula’s executive director. She’s put expenses for the DIY air filters on her credit card the last two summers because climate adaptation is not what they typically do.

And she doesn’t want the group’s focus to drift too much from its main goal of getting people to reduce their climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions. Globally, they are still on track to produce even more catastrophic impacts later this century.

“We’re trying to manage the unavoidable,” she said. “But then, how do we avoid the unmanageable?”

Daniel Lam contributed to this story.

[ad_2]