Scattered across California’s San Joaquin Valley, one of the richest agricultural areas in the world, are colonias—unincorporated communities that are home to some of the Valley’s poorest residents. These communities are overwhelmingly the products of a long history of racism and housing discrimination. And the legacy of racial exclusion that led to their existence, far from being safely buried in the past, continues to manifest itself in daily life. Every time a resident of a colonia goes to a faucet for a drink, the contaminated water that emerges—if any water comes out at all—is a living reminder of that history.

These communities are not passive victims of past discrimination, however. They have organized to demand redress in the form of a clean and adequate water supply, sewer service, and even street lighting, forcing the state’s politicians to listen up. Though it has taken three-quarters of a century, the colonias are now celebrating a victory in their long effort to address inequality.

Access to water is a critical question in California. In 2014, then-Governor Jerry Brown declared a drought emergency in the state. California today is even drier, and the drought declaration is back in force. Teviston, a tiny colonia established by African Americans in the 1940s, went without running water for a month last summer when its only well stopped working. Last year the water table below Teviston dropped 48.9 feet. An hour north in Tombstone Territory outside Sanger, three wells went dry.

Dividing line: Matheny Tract community leader Javier Medina points to the ditch that split the colonia into Black and white sections during segregation. (David Bacon)

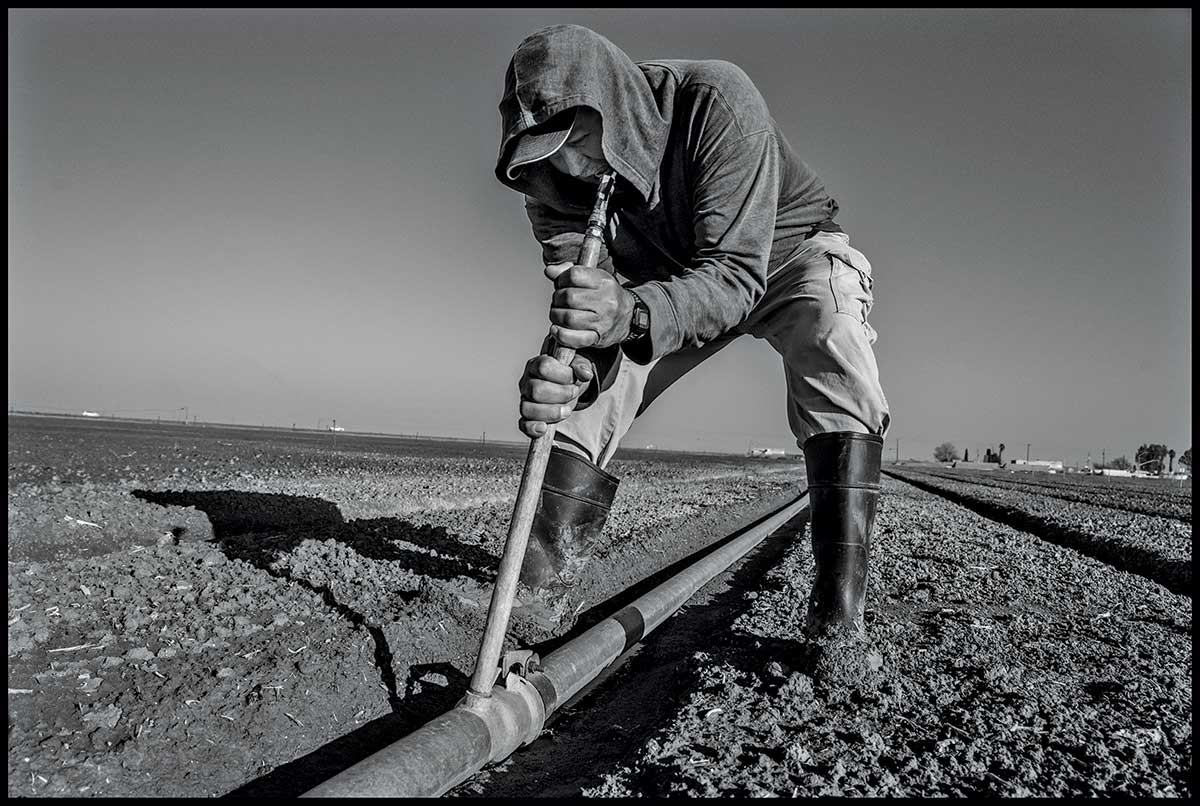

Summer temperatures in the valley, always fierce, can rise to over 115 degrees. Without water, crops would die, and so access to water obeys a hierarchy of power that prioritizes agriculture. Most of California’s water goes to growers, who annually irrigate 9 million acres with 30 million acre feet of water, or 79 percent of all the water in California that’s directly used by people. Residences and businesses come next, consuming 8 million acre feet, mostly in the big cities. Since the early 20th century, taxpayers have funded huge dam and canal systems to service those needs, including the Trinity River Dam, the Central Valley Project, the State Water Project, and the Colorado River Aqueduct.

The colonias hardly count in this calculation. Until recently, their water came entirely from whatever shallow wells their impoverished residents could afford to dig. The wells in some of these communities are now running dry. Tooleville, for instance, depends on two wells that function for only a few hours each day in the summer. It sits next to the huge Friant-Kern irrigation canal that funnels water to growers, but it can’t touch a drop. Growers have pumped so much water from the surrounding soil that the canal has actually sunk, cutting its delivery capacity considerably. In parts of the Valley the land itself is slowly collapsing.

The water crisis reflects a legacy of inequality that took hold during the Great Migration of African Americans from the South at the beginning of the 20th century. As they sought places to live, they were confronted with exclusionary real estate practices, formal and informal, in the urban areas of the San Joaquin Valley.

Related Articles

According to Paul Dictos, Fresno County’s assessor-recorder, the original land deeds were filled with racial restrictions. “I searched the archives and identified thousands of racially restrictive covenants that acted as the mechanism that enabled the people in authority to maintain residential segregation,” he wrote. African Americans arriving from Arkansas settled in Lanare, for instance, because they could not rent or buy homes in Riverdale, two miles up Mount Whitney Avenue. One covenant recorded for a Riverdale development stated, “Neither said real property nor any part thereof, nor any lot nor part thereof, shall be used or occupied in any manner whatsoever by any Negro, Chinese, Japanese, Hindu, Malayan, Asiatic or any descendant.”

That covenant was later voided, and the California legislature passed the Rumford Fair Housing Act in 1963, which outlawed racial covenants and housing discrimination. By then the damage had been done, however, as people had already been excluded from Riverdale and other urban areas and forced to build or rent homes in the colonias on their periphery. Counties and nearby cities provided no water mains, sewer lines, lighting, or, for decades, paved streets. “Being excluded isn’t just about where you can’t live, but where you can,” Dictos says.

Wardell Young’s parents came from Arkansas in the early 1950s. “They worked in the cotton, and I was born in Lanare in 1955,” he says. “They couldn’t live in Riverdale. They’d hang you there and no one would even know.” Sam White, another resident of Lanare, was brought there from Arkansas by his parents in 1952. At first there were no wells, and through the 1960s residents carried water home in buckets and milk cans.

Riverdale had deep wells that produced clean water, but the water under Lanare contains arsenic, which occurs naturally in the San Joaquin Valley’s arid, alkaline soil. When Lanare residents dug wells, White says, county authorities minimized the danger. “We’d complain, and the county would tell us to boil the water,” he recalls. “But you can’t boil arsenic from the water. They say this cuts your lifespan down by two years, and in small doses it can cause Alzheimer’s and rashes. My mother had all that.”

On their own: Vance McKinney and other residents of Matheny Tract organized a committee to secure running water for their colonia. (David Bacon)

Matheny Tract, just outside Tulare, had toxic levels of arsenic in its water for decades. The community was originally a set of ramshackle houses that a local rancher rented out to his workers. At a time when Tulare wouldn’t allow African Americans to buy homes, grower and developer Edwin Matheny sold them, first to his workers and then to other Black families.

“My dad came from Arkansas and found there was work out here,” says Vance McKinney, a truck driver who grew up in the colonia. He was 2 when his father decided to move the family there, and they stole away in the night. “He was a sharecropper, and probably owed money and was afraid of what might happen if the landowner knew he was leaving,” McKinney explains. “When we got here, we lived in a shack. You could climb under the floorboards and go into the house that way.”

Living in the city of Tulare was not possible. “My mom said that the city refused to allow them to have any kind of property,” McKinney says. “The city was fighting them at every turn. You’d try to buy a house, but you had to have papers to prove where you were born, that it was legal for you to be here. But when you left Arkansas, you didn’t bring those documents with you, because you didn’t know what was going to happen.”

There was no running water or sewers for the homes on the dirt streets of Matheny Tract. “We didn’t have those services,” McKinney says, “because we were African American. The county was fighting Mr. Matheny for selling us property.”

A limited resource: Lanare community leader Isabel Solorio uses tap water to wash dishes but has to pay for bottled drinking water. (David Bacon)

Matheny Tract was also segregated. A dry ditch still divides the tiny community. Blacks lived on one side and whites on the other. They were all former sharecroppers who had became farmworkers in California. But as the cotton crop was mechanized, white workers were the first to get jobs driving the picking machines, while Black workers dragged the heavy bags behind them down the rows. Even the kids worked.

Black kids couldn’t walk to the store through the white neighborhood. Their parents, who’d fled lynching and other forms of racial terror in Arkansas, taught their children not to walk alone. “White kids would beat up Black kids,” McKinney recalls. “It wasn’t just the kids—it was the parents too. If you walked across the ditch they’d shout, ‘Little nigger, what you doing over this side? You know you not supposed to be here.’”

Once Black people owned homes, they began organizing, initially to get running water. “Now they had a voice,” McKinney says. “The Blacks got people together in the church here and started a committee. That’s how Pratt Mutual Water Company came into being. Because you can’t speak if you’ve got nothing.”

Four decades ago Tulare County’s general plan stated that colonias like Matheny Tract had “little or no authentic future.” After the Matheny Tract Committee organized to pressure the state with the help of California Rural Legal Assistance, the Water Resources Control Board issued an order for the voluntary consolidation of Tulare’s and Matheny’s water systems. When the city dragged its feet, the state issued a mandatory order, and on May 31, 2016, community activist Reinalda Palma turned the tap, and city water began flowing through Matheny’s water pipes. “It’s been seven years of fighting,” she told the Visalia Times Delta. It was the first time the state had exercised this power.

But the city still refused to connect its sewer system. When it rains, the septic tanks of many homes can’t absorb the water, and sewage bubbles up in the yards. That’s particularly bitter, since Tulare’s water treatment plant is right next to Matheny Tract. “When we complained about the stink, the city said they were using the waste to irrigate nearby pistachio orchards,” says Javier Medina, a member of the Matheny committee.

Today, most of the residents of Matheny Tract are Mexican farmworkers. “There’s a lot of discrimination against Mexicans,” Palma says. “They’ve inherited the problems imposed on Black people,” McKinney adds.

Toolville residents can use the water from their taps only for washing dishes and clothes, but have to buy bottled water for drinking and cooking. One resident puts containers in a rack on the main street through the community, so that neighbors can use them to bring home drinking water. (David Bacon)

Lanare has had less success getting Riverdale to extend its water lines to the colonia. In response, people pooled their resources, dug wells, and built a water treatment facility to remove the arsenic contamination. A few months later, however, the town, short on funds, had to shut it down. Nearly 40 percent of Lanare’s residents live below the poverty line. According to Veronica Garibay, codirector of the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, “It cost $3.7 million, and running it would have meant people paying bills of more than $120 a month. No one in Lanare can do that. So the plant became a symbol, a reminder of what could have been.”

Isabel Solorio, Angel Hernandez, Juventino Gonzalez, and others organized to put pressure on the state to provide some help. They were hopeful, since then-Governor Brown had signed AB 685 in 2012, a bill recognizing that access to drinking water is a human right in California. The state drilled two new wells, installed new pipes and meters, and supplied free bottled water to residents during the construction.

After a year, the water was declared free of arsenic, but it still smells and leaves a residue on sinks and toilets. Residents won’t drink it, and since the state stopped providing bottled water, they’re paying $50 to $70 a month for drinking water. The local water company went into receivership, leaving people on the hook for a system that provides water they can’t drink. “Really, the only solution is a connection to Riverdale, but Riverdale won’t agree,” Solorio says. “The ranchers have pumped the aquifer out. The water table went down to 300 feet in August.”

Tooleville is facing the same problem. Farmers on either side of the community have sunk 400-foot wells, twice as deep as Tooleville’s two wells, one of which has already gone dry. According to Jose Luz Mendoza, a board member of the Tooleville Mutual Nonprofit Water Association, no water comes from the tap at all when growers are irrigating during the day in the summer. Tooleville’s farmworkers, some of whom pick oranges and grapes for the same growers, have to wait until evening to wash off the grime from work.

Cristina Garcia is the community leader who headed the fight to get a water connection to Sanger. (David Bacon)

In 2001, residents of this unincorporated community began asking the nearby city of Exeter to extend its water lines to provide service. Unlike many towns of its size in the Valley, Exeter has a predominately white population, while almost all of Tooleville’s residents are Mexican. Exeter refused. According to Blanca Escobedo, a former organizer for the Leadership Counsel, “In one meeting the mayor said consolidation was a waste of money and he wished Santa Claus was real.” When Tooleville residents attended a meeting in 2019, she says, city council members asked to be escorted to their cars by security. When the community invited Exeter’s mayor and city council to tour the colonia, they wouldn’t speak to residents. “They see us as a community of poor Mexicans,” Mendoza says. “It’s a form of racism.”

Faced with the refusal of cities to redress the human costs of the long history of racial exclusion, unincorporated communities in the San Joaquin Valley began organizing a decade ago. Staff with California Rural Legal Assistance helped organize committees in many colonias and later independently formed the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability. The Community Water Center, based in Visalia, set up the Association of People United for Water. Their common goal was to move beyond the declaration that water is a human right and begin implementing it on the ground. They demanded legislation to force cities and counties to provide the water, sewer connections, and other services that the colonias had historically been denied.

In April 2017 Solorio and Lanare’s water activists began meeting every few weeks at 4 am in front of the dilapidated community center. They’d pile into a car and head down Mount Whitney Highway to Fresno. In front of Garibay’s office, they boarded buses with people who’d driven up from Matheny Tract, Okieville, Tooleville, Poplar, and other excluded communities. Then they’d head up Route 99 to Sacramento.

(David Bacon)

There, they rallied outside the ornate capitol building and then marched inside to testify in hearing after hearing. Water warriors walked the halls of the legislature, demanding meetings with Assembly and Senate members. They found an ally in Bill Monning, a former lawyer for the United Farm Workers and California Rural Legal Assistance, who was elected to the legislature in 2008 and became Senate majority leader in 2014. “Year after year, these caravans came to Sacramento and demonstrated in front of the capitol in the scorching heat,” he recalls. “It was a force that could no longer be ignored.”

In 2019 they finally won what they’d fought for: a law to protect them against drought. SB 200 provides $1.3 billion over 10 years to provide safe, affordable drinking water, prioritizing communities with contaminated or insufficient water, by subsidizing improvements to community water systems or connections to nearby urban areas. Early versions of the bill would have put a small surcharge on water rates to foot the cost, but a ratepayer backlash led to a different funding solution. The bill now uses money collected from polluters in California’s cap-and-trade abatement system to fund what was presented as water cleanup.

According to Monning, about a million Californians in 130 communities lack access to safe, clean drinking water. The vast majority are in rural areas where farmworker families make up most of the population. “In the farmworkers’ union, I’d drive around and find these pockets of workers,” he remembers. “You didn’t need to be a social scientist to realize the inequality between urban areas and these colonias. The difference was clearly racial. The elite suburbs populated by professionals and white people had good water systems. The farmworker communities didn’t have drinking water.”

Monning retired after SB 200 was passed, but activists saw they needed still more legislation to force cities like Exeter to agree to consolidation. “The most cost-effective solution is consolidation, but there’s no will to make the connection,” Garibay says. SB 403, written by state Senator Lena Gonzalez of Long Beach, provides that the Water Resources Control Board doesn’t have to wait until a small water system fails completely before mandating consolidation with a larger one. The board can proactively respond to a community in danger and order the larger community to comply.

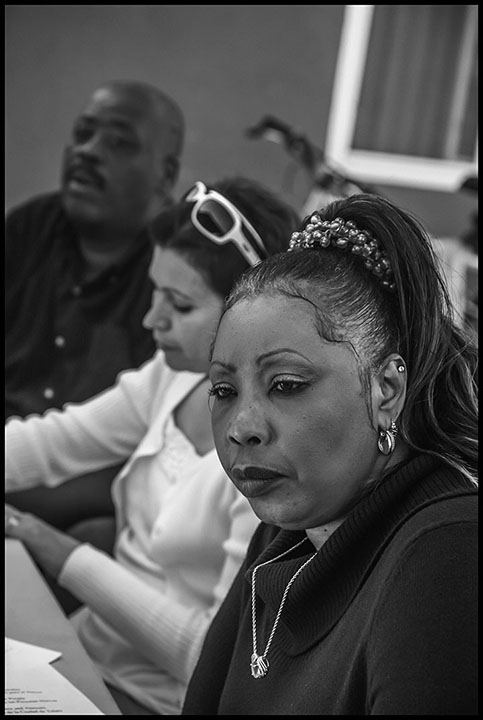

DIY solutions: Irrigator Jose Luis Mora of the Five Points colonia joins community efforts to combat water inequity. (David Bacon)

The caravans and the debate they prompted strengthened the effort to come to grips with the history of housing racism. Three state legislators—Kevin McCarty, Rob Bonta, and David Chiu—wrote AB 1466, which “require[s] the county recorder of each county to establish a…program to assist in the redaction of unlawfully restrictive covenants.” Paul Dictos was already doing this in Fresno, and the rest of the state’s recorders now have until July to set their programs up.

The combination of bills is a start in addressing historical racism, Monning believes. “One reason for taking care of the water and sewage problems of unincorporated communities is to redress the racism that was at the bottom of the reason why they exist to begin with,” he says. “The racist implementation of property laws put at risk disenfranchised communities and has been the cause of cancers, birth defects, and other environmentally caused illnesses—it’s not theoretical.”

The Leadership Counsel plans to introduce more legislation to address these historical inequities, Garibay says. “There’s a racial impact from overpumping, for instance. The groundwater resource plans filed by the counties fail to protect unincorporated communities. Our idea is a bill that can send a message to growers: You can’t continue business as usual. This is our response to the harsh reality of the history of the Valley.”

Because of climate change, the amount of water in California that’s available for human use is shrinking, and the question of priorities remains unresolved. Small communities continue to be at the bottom in the hierarchy of water distribution, and consolidation brings them into larger urban systems with their own problems of rising contamination and falling water tables.

“How do you build equity in a capitalist system into sound land-use planning?” Monning asks. “Planning the strategic use of limited resources and minimizing the use of chemicals makes perfect sense, but the blowback on any such proposal would be phenomenal. They’d say the free enterprise system itself is being threatened.”

In the meantime, Lanare, Tombstone Territory, and Tooleville are still waiting for water from the tap that people can drink.

[ad_2]

Originally Appeared Here